The Most Important Code Isn't Code

Documentation is the single most important change I’ve made to my coding style in the last year.

Documentation is Personal

I’m not talking about injecting a few comments in front of confusing lines here and there. I’m talking about taking a firm, consistent view at how you document your methods, your classes, and your projects, and then sticking to that mentality. Documentation is mostly described as a way to communicate your thoughts to other developers, but honestly, other developers can eat it. Documentation is the best way to communicate your thoughts to yourself.

Documentation is Clarity

If you don’t have an absolute clarity in the code you’re pushing, it rears its head by way of bugs, confused coworkers, and slow code. Straightforward documentation has given me that clarity.

I typically hate process. From TDD to BDD to Agile to everything else, it usually feels too cumbersome for me to stick with it. But two mentalities have really impacted me: TomDoc and Readme Driven Development. Both were designed by Tom Preston-Werner. Both have documentation at their core. Though they’re both obviously helpful for other developers who look at your code, I’ve found them to be extremely helpful to me as I code.

Writing the README first means you think about the end-product first. That seems somewhat silly — I mean, I’m writing this library, don’t I already know what’s coming next? But that’s usually not the case. More often than not I would jump straight into the challenging part of the project since I thought that’s where the substantive part is. It’s not. The end result is always the substantive part of your project. Forcing myself first to consider the API, the interface, and the end result led to a clarity that inspired less code and a more impactful project.

I feel similarly about TomDoc. TomDoc is a mentality that places emphasis on clear, straightforward, explicit documentation. Here’s a simple example taken from the TomDoc spec:

# Duplicate some text an abitrary number of times.

#

# text - The String to be duplicated.

# count - The Integer number of times to duplicate the text.

#

# Examples

#

# multiplex('Tom', 4)

# # => 'TomTomTomTom'

#

# Returns the duplicated String.

def multiplex(text, count)

text * count

endYou describe your method arguments, and you detail your response. Every time. It can sometimes feel repetitive, but that repetitive feeling is one of those I strongly welcome. It improves the clarity of my code. I get more done in less lines. The documentation style itself is clear, too. I write this blog in John Gruber’s Markdown because Markdown looks and feels like plaintext. I use Tom Preston-Werner’s TomDoc because TomDoc looks and feels like plaintext. There’s very little interface to learn between writing it down and rendering it in your head.

Documentation is Testable

Documenting code in TomDoc has lead me to two big testing personal “breakthroughs”, if you will. Since you’re required to detail every method argument, you’re forced from the beginning to consider how those inputs end up impacting that method. You think about the edge cases explicitly. Conveniently enough, those edge cases almost always translate into real test cases. I don’t consistently TomDoc first or write my test first, but they almost always happen simultaneously, since they effectively work in tandem. One helps you write the other.

My second “breakthrough” is realizing that if some method is hard to document, it’s too big. Ruby in particular has been harping for years that you want short, focused methods. I know that. Everyone’s known that since their third week using Ruby. But even if you’ve been writing Ruby for years, you can pretty quickly fall into the classic “oh I’ll just handle this here too” mentality. Once I do that, I end up trying to document more method arguments, more possible method outputs, and it’s just more work. Once that happens, it’s an obvious reminder that I messed up this method and should break it into two or three other methods. That means smaller, more resilient and easier-to-test methods, which directly translate into less brittle code.

Documentation is Diffable

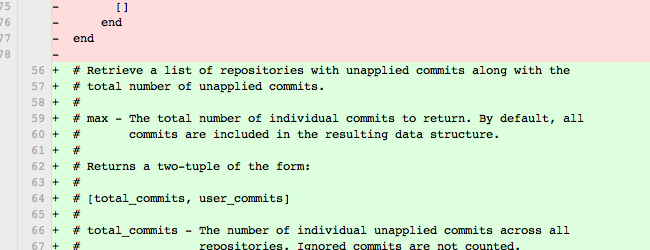

Over the last year or so, we’ve been adding more and more TomDoc to code that we push here at GitHub. It’s not high priority or anything, but if you refactor or touch old code, it’s nice to add documentation for it.

We’re now at 30-plus employees, and there’s a lot of code flying around. When someone pushes to a GitHub repository, Hubot, our trusty Campfire bot, jumps in and posts a Compare View of the changes:

This hook is important. It’s how everyone at GitHub can see how GitHub is changing incrementally. The commit messages in Git are helpful to see what’s happening, but sometimes the commit message and (particularly!) the code doesn’t really give you a good idea of what or why something is changing.

Seeing the changes in a huge block of documentation in the Compare View on GitHub ends up being much easier to parse. You can see which arguments got removed, which new edge case is defended against, what changes are made in the public API. It’s another tool in your belt to help communicate code changes to everyone else.

Documentation is Marketing

I love the idea of documentation as marketing. A good README gets people to jump into your project much, much quicker. Heavily-documented code means others can read your project much, much quicker. Heavily-documented code means others will tend to break your tests less.

This extends to project websites and documentation as well. In fact, I love this documentation-as-marketing concept so much that I wrote about it. Even though I get a lot out of my documentation, that doesn’t mean that it can’t serve as a promotional vehicle for my project, either.

Documentation helps you in the bedroom

Well, I’m still trying to test the validity of that. But documenting your code is cool as hell. More importantly, it makes me feel more confident about my own code. You don’t need to go full-bore Readme Driven Development, you don’t need to use TomDoc, you don’t need to follow any particular process. But improving your documentation skills will make you a better developer.